| We followed him out of the house and back to a

half-finished building about 25' wide and perhaps 200' long with

occasional doors, windows and garage doors which served, at various

distances back, as music store, repair shop, guitar factory, and garage.

We passed a lovely pond in the middle of a nicely kept lawn and flowers,

nestled up against the house. The serenity of the pond was only somewhat

disturbed by the mannequin legs sticking straight up from the center. Near

the lake was a small white tombstone with the legend: "Here Lies Mary

Thomas, Guitared to Death." Something seemed odd about the giant Douglas

Firs gently swaying in the distance. Perhaps it was the fact that they

were hung with guitars, giving the impression of Christmas tree ornaments.

Across a patch of mud and into the door of the shop. We were met by an

aroma mainly consisting of cigar smoke, walnut dust, and fresh lacquer.

Here were row upon row of guitars hanging from rods, as well as

amplifiers, tools, car parts, furniture, and hand-drawn pastel posters

singing the praises of "Thomas, the Cadillac of Guitars". Bumper stickers

advertised country radio stations and artists, notably Buck Owens who was

still a regional act. On a Honda 50 next to the counter sat a life sized

dummy with the grotesque, pop-eyed face of a hanged man. Over the years

this guy really got around, now seated in the living room, now lynched in

the yard, now driving the company car.

Harvey stood behind the counter in front of the mysterious and

forbidden door to the rest of the shop. It was years and dozens of visits

later that I was first invited back through that door. I eventually worked

as a repairman for Harvey.

I brought the plywood body sections and fretted neck out of a paper

bag, and haltingly explained that I just needed a pickup to complete the

project. Harvey gravely picked up the fruits of my labor and examined them

silently for a few minutes as the cigar moved by some curious process from

one end of his mouth to the other. Then he spoke.

"Do you have a fireplace?"

"Ah...No, but we have a trash

burner."

"That will do fine. Put this junk in it and burn it. Then if

you want me to show you how to make a guitar, I will."

Gulp.

Mom was furious, but thankfully didn't hit him or anything. I was

abashed but determined. Over the next two and a half years, (and dozens of

drives to Midway thanks to the ever-supportive mom and dad) I did finish

an electric bass under his tutelage. Actually, he did half the work

himself, back in the inner sanctum. He never really explained anything.

Rather, he Socratically allowed me to chip loose little gems of info as I

needed them. But only when I needed them

Harvey had a thing for Cadillacs. There were usually one or two

bulbous, toothy, mid-fifties hearses in the driveway. These were generally

black with white roofs and white stencil lettering saying "Thomas Custom

Guitars." Farther back, by the shop's garage doors, there would be an ever

changing herd of vehicles consisting mainly of Caddies from the '50s and

'60s, but also including the odd pickup truck and speedboat. This flock

was shepherded by a '40s vintage truck that was somewhere between a tow

truck and a crane. The farther back in the driveway one got, the more (and

worse) Cadillacs came in to view. The swamp was populated with cars,

hearses, trucks, busses, and trailers, and every turn around a tree or a

clump of blackberries revealed yet another group of treasures. Dry places

between the ponds formed a labyrinth which described a sort of hierarchy:

Those cars which were not called forward periodically by the crane became

surrounded by poplar saplings and slowly went back to nature.

These

vehicles formed one aspect of Harvey's vast trading stock. He constantly

traded cars, busses, guitars, cash, and tools for each other in any

combination and always came out ahead. I should know.

I was an 18 year old long haired freak when I started working at

Harvey's shop, a fact Harvey was fond of pointing out in a redneck way.

Actually, I felt a kind of kinship of outlandishness with him and his

crowd. Although the hardcore Grand Ole Opry aesthetic that prevailed at

the Thomas compound was older and better established than the hippie

style, it was just about as far from the polite mainstream. My car had a

brilliant sunset scene covering its roof and back end. Harvey drove a two

tone hearse. Which is freakier? Of course, to his way of thinking he was a

responsible, conservative citizen while I was some kind of radical.

True to my freakish ethic, I did not have reliable transportation for

the 50 mile daily round trip. My 1961 Volvo 544 humpback didn't have a

starter, and it was too flat there in the swamp to pop-start it.

"I've

got a Volvo starter for you", said Harvey, and pointed to a Ford.

Huh?

Is there a Volvo starter in the trunk, or... Oh. I get it. That Ford could

start my Volvo by pushing it. Ha, ha.

I looked away from the Ford and

back at Harvey to find his beady eyes fixed on me. He was intently ticking

away the seconds, sizing me up by seeing how soon I would get the joke. He

did this quite often. When he saw me finally catch on, he would roll his

eyes in pity for the poor, thick hippie. "Sheesh!"

Another time he suddenly stated:

"Got a job for you. Need a wooden

box one inch by one inch by fifty feet. (pause.) Guy wants to ship a

garden hose." Tick, tick, tick. "Sheesh!"

One day Harvey gave me some advice on guitar playing.

"The secret of

playing the guitar is to move your hands as little as possible. That's the

mark of a real pro."

It sounded nonsensical at first. Then he began

playing "Winchester Cathedral" just the way Chet Atkins would have done

it. The full-blown arrangement flowed out easily from the short, powerful

fingers that barely moved. Shifts up and down the neck were accomplished

in a slow, flowing motion, and the picking fingers traveled a scant

quarter inch. It all gave the remarkable effect of a pantomime. He sat

still as a statue, drilling holes in your head with his characteristic

glower.

The fact that Harvey's Country Western milieu was utterly foreign to me

did not mask the fact that he was an accomplished guitarist and a

consummate performer. His guitar making grew out of his former career as a

machinist and his lifelong involvement with country music. Harvey played

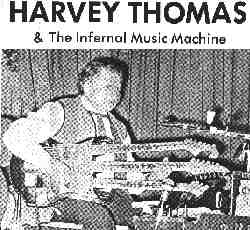

the regional country lounge circuit as a one man band. On stage he would

sit on a bench behind "The Infernal Music Machine", a box containing his

various amps, reverb springs, tape delays, flashing lights, and one of

those old style rhythm boxes with the buttons marked "samba", "waltz", or

"polka" which would give you one bar of little clicking sounds repeated to

infinity. A set of electronic organ pedals lay beneath his feet.

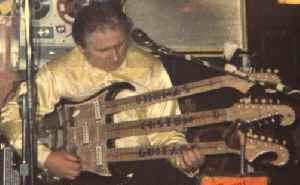

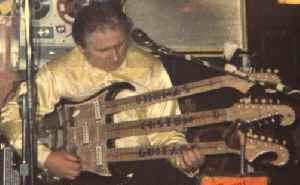

The centerpiece of Harvey's on stage hardware was his triple neck

guitar, which featured a standard six string with vibrato tailpiece on the

bottom, a twelve string in the center, and a short scale six string bass,

also with whammy, as the top neck. Above this considerable fire power,

Harvey would sing country standards, for instance:

The old town

Is upside down

As I

look up

From the ground

'Cuz I'm lying

Where the brakeman

lately threw me

Down the road I look

And there goes Bessie

Good old cow

But

kinda messy

that's why we've got

Such green, green grass back

home

|

Click to see Harvey at the controls of the Infernal Music Machine.

|